Photocopiers Terrified the Publishing World

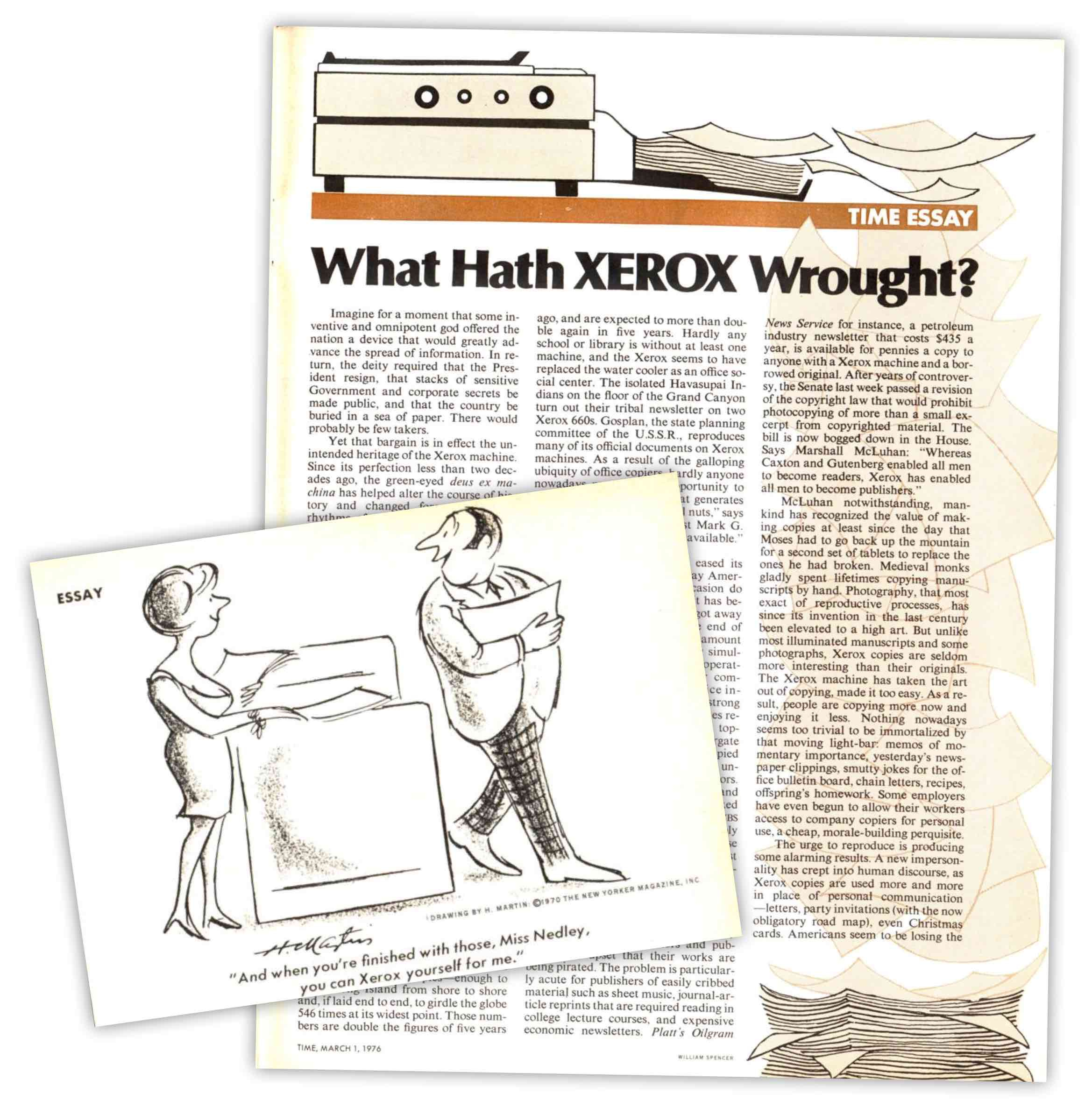

“What Hath Xerox Wrought” asked a 1976 Time Magazine headline

“What Hath Xerox Wrought” asked a 1976 Time Magazine headline, the proceeding article prompted readers to imagine if: “some inventive and omnipotent god offered the nation a device that would greatly advance the spread of information.”

There was a catch though: the promethean powers afforded by this “green-eyed deus ex machina” would also bring chaos: “In return, the deity required that the President resign, that stacks of sensitive Government and corporate secrets be made public.”

The writer was of course referring to the Watergate scandal and Daniel Ellsberg’s use of photocopiers to leak the Pentagon Papers to the press. The hypothetical was actually a reality. While the USSR kept strict control over the technology, highly regulating the machines until 1989, the free world was left to deal with the ‘consequences’ of freedom.

Downsides of this supposed double edge sword - cited in Time - would be encouraging waste and slothfulness, on top of stifling creativity and punching holes in copyright laws. This last issue was of particular concern to publishers and authors, one that had been growing for more than a decade because, as Marshall McLuhan would put it in 1977, “Gutenberg made everyone a reader, Xerox made everyone a publisher…”

A 1963 article - syndicated throughout the US - painted a damning picture of the future copy machines would bring upon publishers and writers: "…the authors and book publishers of America are beginning to suspect that what is meat for the photocopying industry will turn out to be poison for writers."

The piece noted stories circulating in the literary world about a Texas professor creating custom anthologies for his students, thereby "cheating poets and short story writers of anthology fees." The author cautioned that "The photocopying threat brings the technological revolution home to writers, who are among the last individualists among us," which "would serve to make the life of the freelancer more hazardous than it is at present."

Scientific publishers felt threatened too, the author noting "it poses a menace to the livelihood of scientists. Publishers of scientific material...stand to lose in the very near future if a few more pennies can be shaved from the cost of photocopying." One publishing executive - Curtis Benjamin of McGraw-Hill - warned scientific progress could suffer if the market was impacted. Libraries found themselves at logger heads with publishing companies, as they became popular places to access photocopying machines.

The author called for a new Mark Twain to emerge, who had helped lead a movement in the past to “hammer out some universally valid copyright laws against the international pirating of authors' material.”

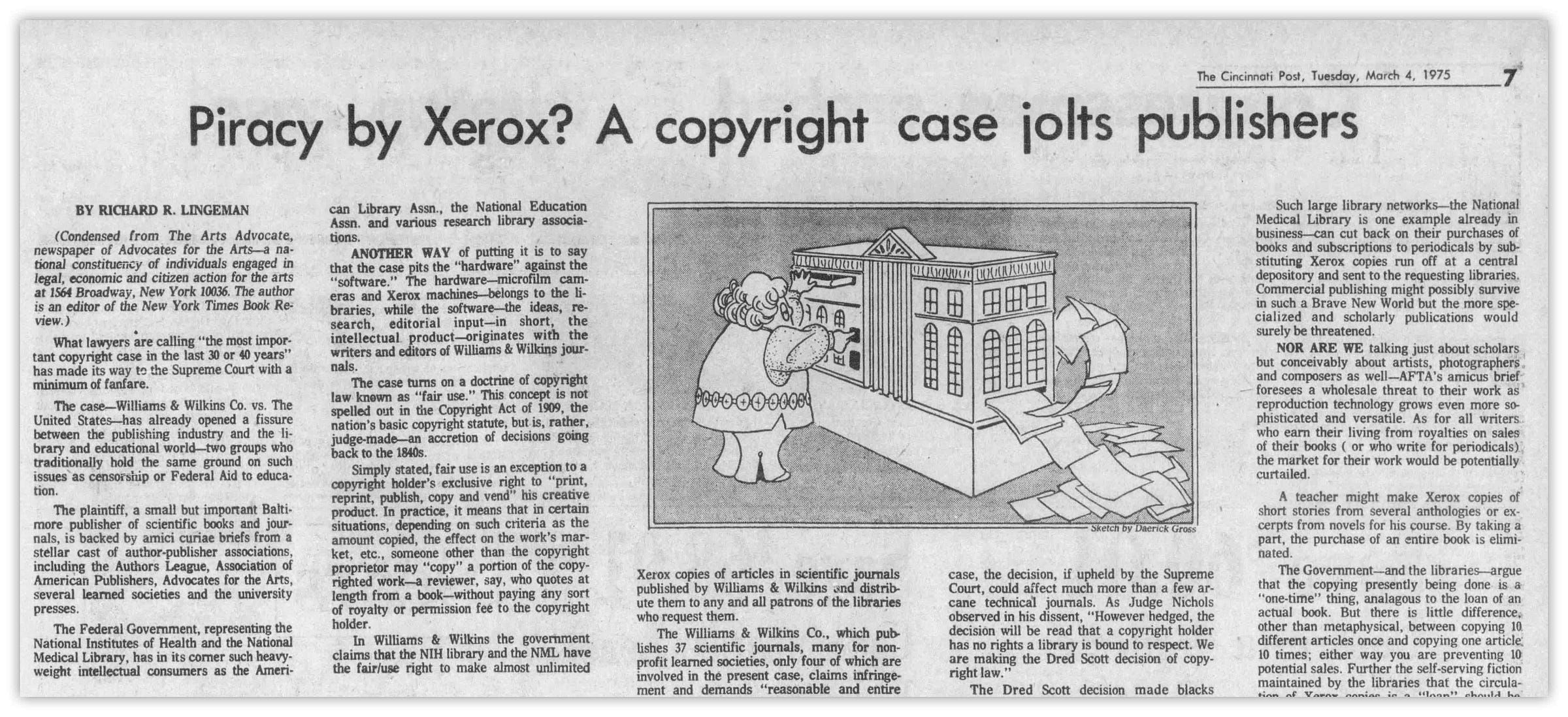

In 1968, a publisher stepped up to the plate, and sued the government (specifically the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health) for photocopying and distributing its materials. The publisher lost, then appealed, the Supreme Court ruled against it again setting a new and important precedent for the concept of ‘fair use.’

In 1976 the Copyright Act was up for revision, libraries would lobby for exemptions - citing the case - they didn’t get a blanket exemption, but did get some allowances for patrons who want to reproduce work for research, as well as replacing and preserving documents - among other things.

Only 7 years later ARPANET would launch, a computer network that would eventually evolve into the internet, making the threat of photocopiers and physical reproduction seem quaint to publishers.

Feel free to reproduce this newsletter infinitely.

Other NEWART articles:

Art Has Always Been Artificial

Written in collaboration with Freethink for their Special on Creativity & AI. Originally published there.

Warhol Would Have Embraced AI Art

Andy Warhol was enamored with the first computer he ever owned—and he didn’t seem all that worried about the risks of disruption. If there’s any famed artist who would likely “get” the power of generative AI for creatives right from the jump, it’s likely Andy Warhol.