The Forgotten War on Beepers

Before smartphones, beepers were in the crosshairs of parents, schools and lawmakers

30 years before parents and lawmakers sought to save youth from smartphones via age limits and bans in schools, a similar conversation took place about a pre-cursor to the cellphone: pagers

Through the 1980s pagers became increasingly popular with teens, and also: drug dealers. This fact would eventually drag the gadget into the existing moral panic about adolescent drug use of the era.

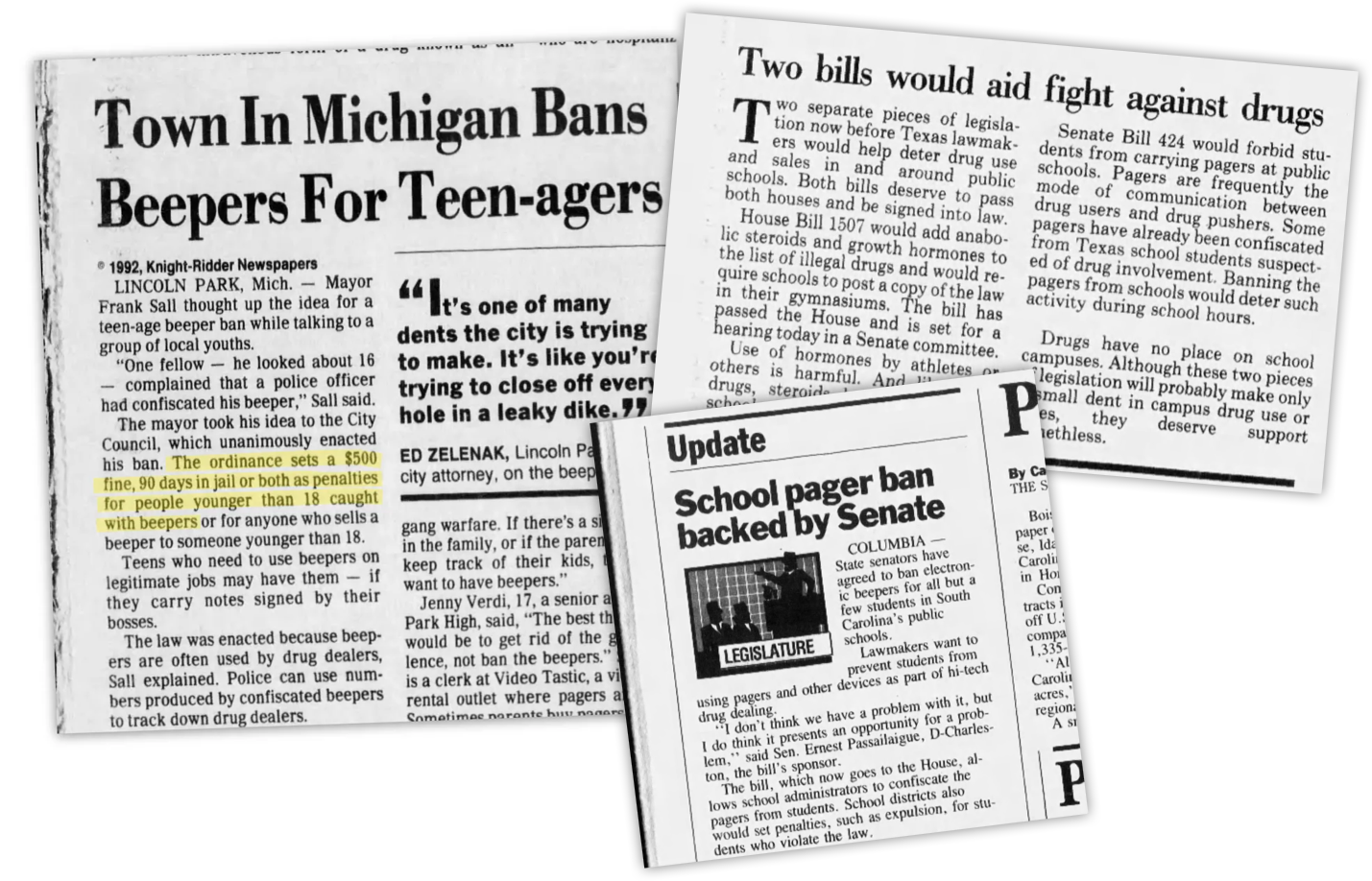

The pager panic began with a 1988 Washington Post report on the gadgets prevalence in the drug trade, quoting DEA and law enforcement officials. The piece was syndicated throughout the US under headlines like “Beepers flourish in drug business” , “Beepers Speed Drug Connections” and “Drug beepers: Paging devices popular with cocaine dealers”

The spread of the story stoked concerns that beepers in the hands of youths weren’t just a distraction - a common complaint from teachers - but also a direct line to drug dealers. One school district official told The New York Times: "How can we expect students to 'just say no to drugs' when we allow them to wear the most dominant symbol of the drug trade on their belts."

"How can we expect students to 'just say no to drugs' when we allow them to wear the most dominant symbol of the drug trade on their belts" - James Fleming, Dade Public Schools, The New York Times, 1988

In response schools, towns and states would pass rules against beepers. New Jersey prohibited beepers for under-18s entirely, possession could result in a 6-month jail-term - a law proposed by ex-policeman and Senator Ronald L. Rice.

A city ordinance in Michigan mandated 3-month jail terms for children caught in possession of one within school grounds. Chicago passed a ban that its Public Schools Security chief said would also reduce prostitution:

"We've got girls 11 years old. They get a call and they're out of school to turn a trick” - George Sims, Chicago Public Schools Security Chief , Associated Press

Other states proposed community service, fines and 1-year drivers license bans as punishment. Thousands of of young people were victims of these heavy handed prohibitions - some of which made headlines:

Some schools regularly referred students found with pagers to police, one 16-year-old - Stephanie Redfern - faced a disorderly persons charge. A 13-year-old was handcuffed. Chicago was particularly aggressive in its enforcement: over 30 children were arrested and suspended for ‘beeper violations’ in one police sweep at a school - many parents couldn’t locate their kids for more than 6-hours. This was just the start:

According to Police Lt. Randolph Barton - head of the Chicago public school patrol unit at the time - by April 1994 there had been 700 beeper arrests in Chicago schools, with the prior school year seeing 1000. Some still felt these numbers were too low:

“Right now I don’t think enough people are being arrested for wearing or bringing beepers into Chicago schools” - Ald. Michael Wojcik (35th)

In 1996 a 5-year-old in New Jersey was suspended for taking a beeper on a school trip, outrage ensured - catching the attention of Howard Stern, leading to calls for the laws to be amended or repealed.

Even young adults didn’t escape the beeper prohibition: 18-year-old Anthony Beachum feared a jail term after trying to sell a beeper to a student on school grounds. State prosecutors sought a criminal conviction for Beachum - that would have barred him from his hopes of joining the military. The judge settled for probation and 10 hours of community service.

Hampton University required students register beepers with campus police, even though there was no evidence of them increasing drug access. VP of student affairs at the time would admit as much:

“There is not a single case where I can make a connection between beepers and drugs” - Hampton University, VP of Student Affairs

BIG BEEPER FIGHTS BACK

The beeper backlash was a BIG problem for Motorola who had 80% of the pager market at the time. The company had a hit on its hands - that was introducing the brand to a whole new generation - so in 1994 it fought back, partly by rallying youth. A move reminiscent of TikTok’s recent lobbying tactics.

Motorola enlisted children of its employees to help design pro-beeper campaigns, emphasizing the importance of pagers as legitimate communication devices for the young. “Who better to help plan for the battle than teens themselves” one report on the efforts would say. At a week long event, one attendee came up with the slogan “Pages for All Ages.”

The company ran television ads promoting pagers as a tool for child parent communication and in 1996, partnered with PepsiCo to offer 500,000 pagers to youths at a low price.

The promotion angered lawmakers - like State Senator Ronald Rice - who’d been a leading player in the war on beepers. Around this time moves to over-turn bans emerged, by other lawmakers calling them outdated - partly fuelled by the suspension of a 5-year-old alluded to earlier. New Jersey would amend the law in 1996, but not repeal it.

3 decades later, the New Jersey law was still on the books. The original sponsor of the bill - Senator Ronald Rice - sought to repeal it in 2017 saying "Fast forward almost three decades and it's no longer an issue."

There is little evidence it ever was an issue, in-fact - the subsequent rise of cellphones in schools coincided with a massive reduction in youth drug taking, while causation has been suggested by some - it certainly serves as stronger evidence against the idea of mobile messaging increasing drug access.

Senator Ronald Rice passed away in 2023 - the New Jersey Pager ban still in place - months later The Washington Post editorial board would call on schools to ban cellphones entirely - part of a new moral panic about kids and digital devices, many of whose parents were once prohibited from bringing pagers to school.

Nod to Ernie Smith of Tedium.co the only other person to cover the beeper bans, a piece that helped highlight a few fun examples included in this piece

I have fond memories of mine although others did seem to lean towards thinking I was a drug dealer, as a result!

"it certainly serves as stronger evidence against the idea of mobile messaging increasing drug access." - who needs access to substance anyway when the device in your hand makes you just as high?