1920s

The rise of horseless carriages, mass production and other new forms of automation in the first two decades of the 20th century created anxieties about the future of work and employment. A short and sharp depression in the first year of the new decade helped create unease too.

In a 1922 commencement speech at Wellesley College, President of the Rockefeller Foundation - Raymond B. Fosdick pondered: “Can education run fast enough” for people to beat the machines. A number of books would be written regarding the subject. ‘Social Decay and Regeneration’ - published in 1921 - would be reviewed by the New York Times under the title ‘Will Machines Devour Man?’, accompanied by an provocative illustration of someone being fed into a sausage making machine.

By the end of the decade The Times would be publishing editorial implying the worst case scenario may be manifesting, with data and charts coupled with illustrations of long unemployment lines, it blamed automation for workers’ “idle hands.”

1930s

The start of the Great Depression and the subsequent mass unemployment must have seemed like the fulfillment of the popular prophecy of the previous decade (and century): that automation would eventually render too many unemployed and cause societal disorder. Without a concrete cause for this sudden and shocking economic turmoil, even societies greatest thinkers would reflexively finger automation as a key cause.

Einstein implied as much in 1931 when he blamed the “great distress of current times as the result of man-made machines”, while Keynes would cite automation as a key part of the present economic strife saying “We are being afflicted with a new disease, technological unemployment.” The term was a timely neologism that would quickly be adopted.

The rise of recorded sound and its visible impact on musicians was widely reported and offered corroboration to concerns. The ever growing concern prompted Henry Ford to write an op-ed in The New York Times ‘World’s Fair Edition’, defending machines and automation in which he’d say: “There are those who appear honestly to think that the only way to return idle men to work is to destroy the one thing that makes their jobs possible.” He pushed back against a tax on automation, noting that for every job taken, 100 new ones are created - citing his Ford Motor Company as an example.

🎙️ Here excerpt of Hear Ford’s essay read by AI:

1940s

As the 1940s began, the President of MIT, Karl Compton, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt publicly disagreed over the impact of automation on employment. Compton pushed back on Roosevelt’s recent warning to congress that the country had not yet found a way to deal with the surplus labor created by ever increasing modes of automation.

The same year, Senator Joseph C. O'Mahoney proposed the idea of taxing employers using more than average automation to address the loss of tax revenue from displaced workers. While Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Hal Boyle wondered “Who will have the last laugh in the gadget age — man or machine?,”

1950s

Increased automation - including Ford Motor Company replacing assembly line workers, and the advent of automatic elevators - would renew concerns. Fears in the UK over a “robot revolution” swelled, while in US calls were again being made for congress to investigate automation. President Dwight Eisenhower dismissed ‘‘deplored’ fears of automation in 1955, calling them groundless, saying the same fears had “plagued people for 150 years and always proved groundless.”

The United Nations International Labour Organization would investigate the subject too, in a New York Times article the Director of the investigation wondered: “is the possibility of a completely automatic factory operating without human hands and governed primarily by electronic "brains." This would foreshadow the next great automation panic coming in the following decades: computer based automation. A short but sharp depression at the end of the decade was termed the “Automation Depression” by The Nation.

1960s/1970s

The election of President Kennedy in 1960 intensified the focus on technological unemployment. The Kennedy administration took automation concerns more seriously than its predecessor, with the US Secretary of Labor warning of workers being left on a "slag heap." 1961 would see Time Magazine publish an article titled ‘The Automation Jobless’ and predictions were made that automation would end most unskilled jobs. One professor predicted counter revolution.

Even white collar workers felt unease, with innovations like ATMs threatening bank tellers, and photocopiers being called ‘poison’ to writers, publishers and academics. In response to the hysteria, business guru Peter Drucker penned an article defending automation, arguing what Henry Ford, Karl Compton and President Eisenhower had before him: “Although automation does cause job losses in some plants and industries, its over-all effect is to create more jobs than it destroys.”

In 1965 Time Magazine would run another story on the subject, this time on its cover: ‘the computer in society’, contained within it a prediction by a economist that echoed Keynes in the 1930s: automation would lead shorter work weeks.

The 1970s saw a marked acceleration of the digital revolution, as technological advancements began to permeate various industries. Many workers became concerned about the implications for their job security. Across the Atlantic UK Prime Minister James Callaghan sought the help of a think tank to investigate the potential impact of these new technologies on employment.

1980s/1990s

The computer age and advances in robotics perpetrated a cycle of fear in the 1980s. The New York Times issued a cautionary warning in an article titled ‘A Robot is After your Job’ and some economists wondered if ‘full employment’ would ever be possible again. White collar workers again feared their days were numbered.

In 1995 Jeremy Rifkin would release his book ‘The End of Work’, foretelling a ‘post-market era’, warning that the roots of societal crime are a ‘workless world’ and as this trend continues it “threatens to undermine the very foundations of modern society.” For perspective the United States just posted its best employment numbers since the 1960s. Rifkin would move on catastrophizing about Genetically Modified Foods, helping start a global movement against it.

21st Century: 2000s, 2010s, 2020s

2000s: The dot-com crash and subsequent economic downturn dampened enthusiasm for technology. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan issued a warning regarding the impact of technology on employment, setting the stage for a new wave of concern.

2010s: The raid development of self-driving cars created new concerns about technological unemployment. Google, Elon Musk and Rideshare services all made optimistic predictions that a self-driving revolution was in the offing. This prompted Bill Gates to propose a robot tax - something that some economists strongly opposed at the time.

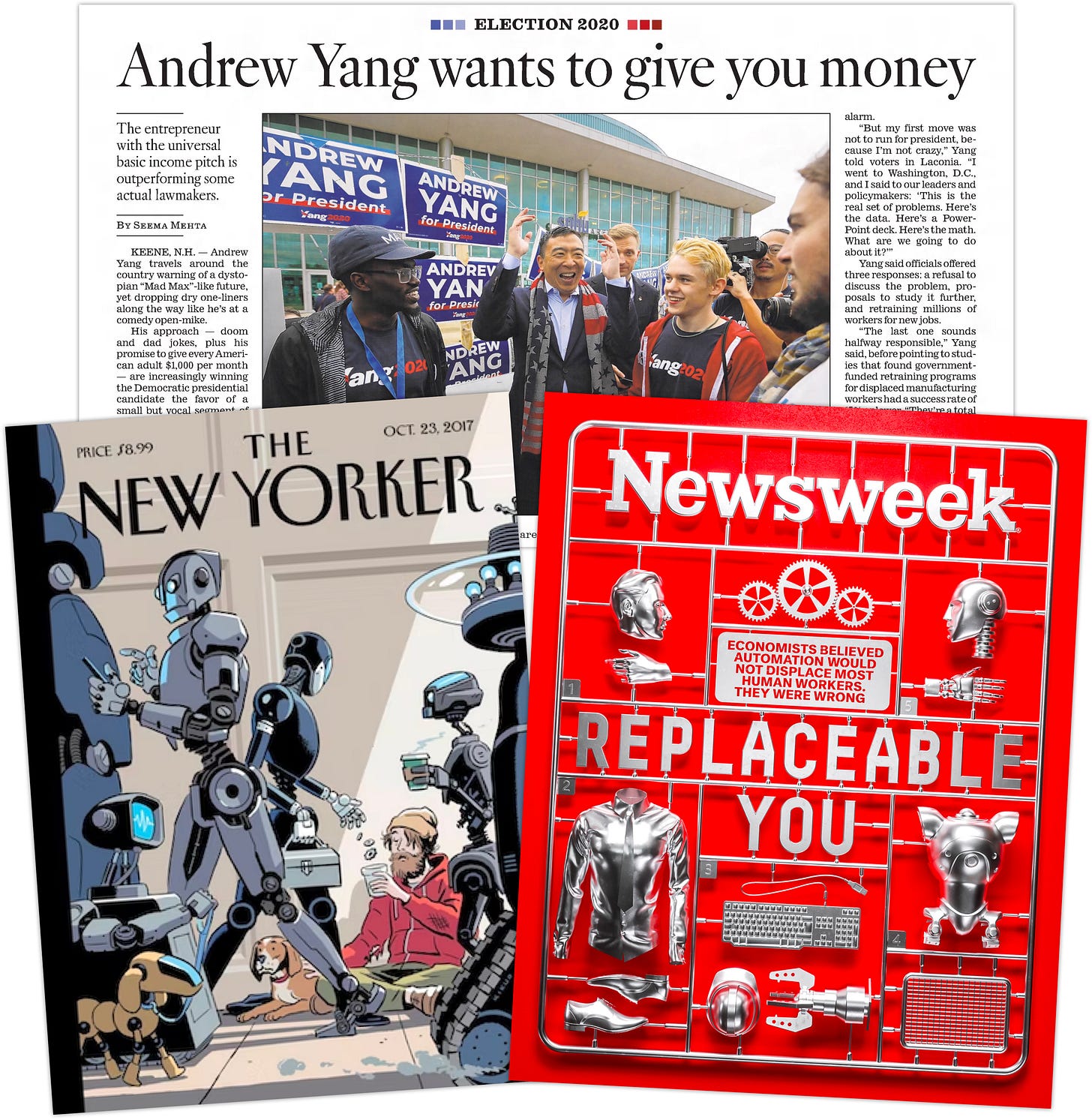

2020s: With Elon Musk and Tesla seemingly unstoppable, and a freshly announced Tesla semi-truck with self-driving capabilities, the threat of automation again felt like an ebbing threat. Andrew Yang would propose a novel solution to the growing unease in a campaign promise for his 2020 presidential run: basic income. One of his predictions was that truck driving - one of the biggest form of employment in the US - was soon to be automated. This would re-introduce the idea of technological unemployment into the mainstream discourse. Economist Paul Krugman would push back on the idea.

In 2022 and 2023 the emergence of ‘generative AI’ kicked off a new spike in concerns and fascination with the future of employment and automation. Bill Gates would again propose a robot tax, along with unlikely ally Bernie Sanders - while Andrew Yang would seize a moment of uncertainty for another Presidential run.

As in the past, the debate isn’t about wether technology will take jobs, it is about how fast it will take them and how many it will create. It is much easier to imagine someone losing their job to a new technology, than it is to imagine many people gaining jobs that haven’t been invented yet.

This was REDUNDANT, a project by Pessimists Archive exploring the history of fears about technological unemployment. We will be publishing 10 posts for the last 10 decades exploring fears of automation.

Subscribe for more posts:

For more content about the history of fears of technology, subscribe to Pessimists Archive:

The difference this time, is we're automating human cognition, which really leaves nothing left for us. The only equivalent in history, was when cars replaced horses. We're the horse now.

But this time, this time is different