Einstein Blamed Automation for the Great Depression

Not even Einstein was immune from the Lump of Labor Fallacy...

Amid the turmoil of The Great Depression, one of history’s great intellectuals shared a very unintellectual hot take: he blamed automation for taking all the jobs and causing the economic chaos that would define the 1930s.

His name? Albert Einstein.

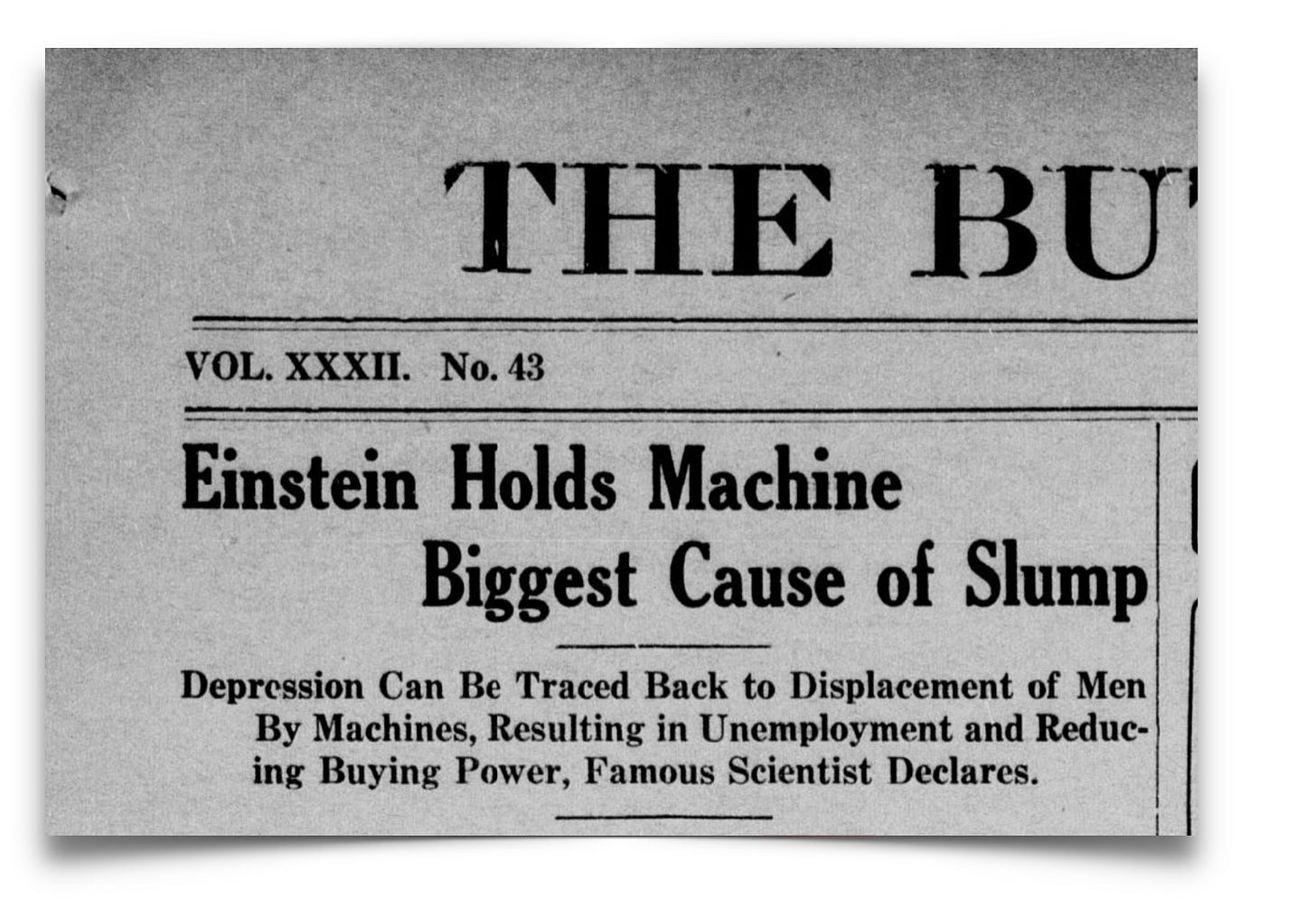

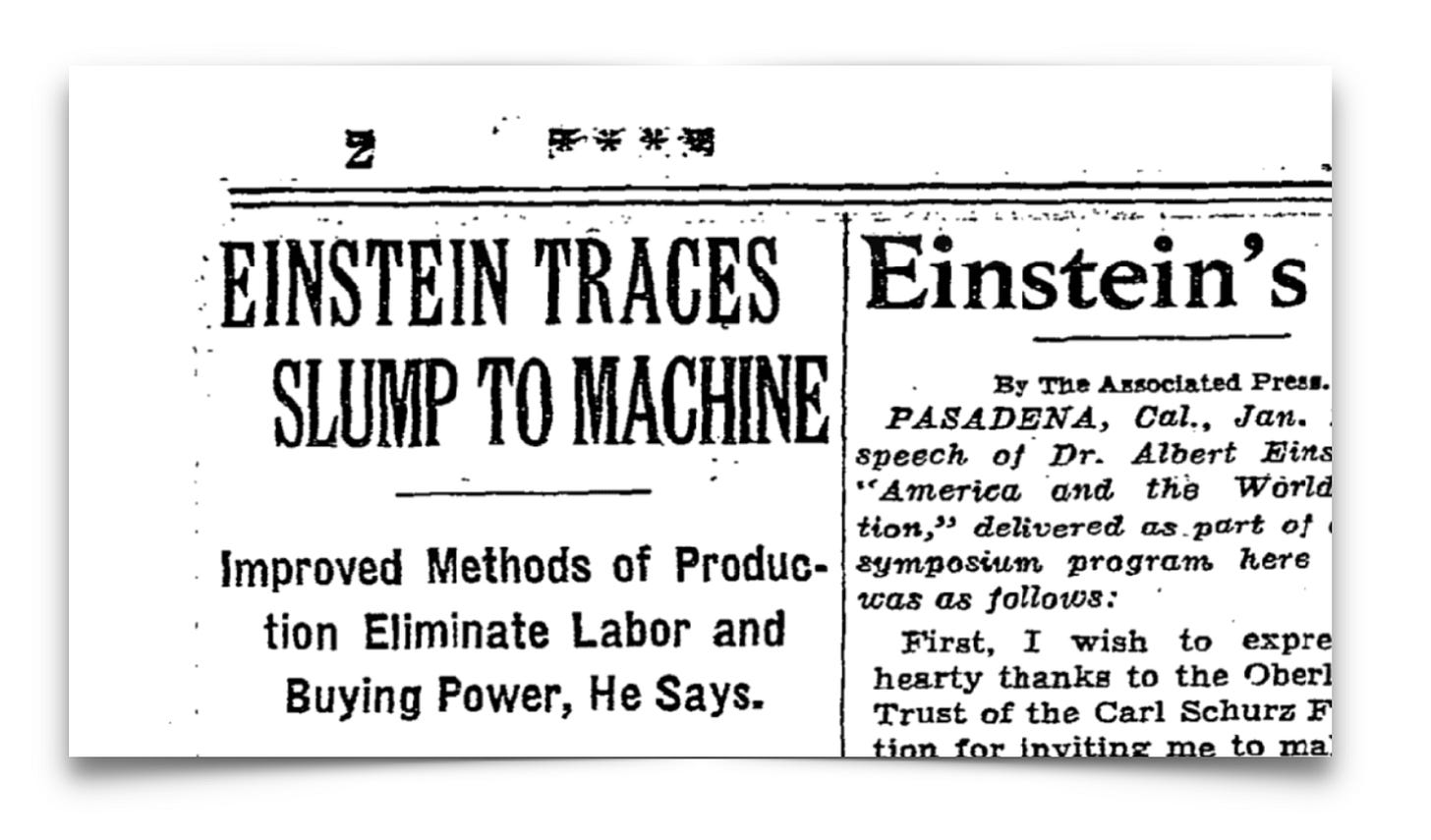

In a 1933 speech the famous physicist argued that automation — rather than war debts—were the primary causes of the economic turmoil in his home country of Germany, and the United States. The speech titled ‘America and the World Situation’ was covered by The New York Times under the headline "Einstein Traces Slump to Machine":

On the same page was a full transcript of the address in which Einstein stated his thesis:

“According to my conviction, it cannot be doubted that the severe economic depression is to be traced back for the most part to internal economic causes: the improvement in the apparatus of production through technical invention and organization has decreased the need for human labor, and thereby caused the elimination of a part of labor from the economic circuit and thereby caused a progressive decrease in the purchasing power of the consumer.”

His evidence? The United States was also in a depression, without the crushing war debts Germany had - however, both countries were seeing rapid automation in their economies: the common denominator in his mind. It was a diagnosis he’d hinted at years prior in a 1931 Berlin speech that blamed the “great distress of current times as the result of man-made machines.”

He wasn’t alone. Only a year prior economist John Maynard Keynes popularized the term ‘Technological Unemployment’ bringing the notion attention shortly after the start of The Great Depression. While Keynes would consider automation a factor in the downturn, he was optimistic in the long-run for it to improve quality of life and reduce working hours. Einstein didn’t seem to make any such optimistic caveats.

Einstein stressed that identifying automation, rather than post-war debts - as the key cause of economic strife would ease tensions between nations and reduce “a dangerous source of mutual embitterment of nations.” This was no doubt an allusion to the ‘The Treaty of Versailles’ (blamed for Germany’s economic turmoil by Adolf Hitler.) A week after Einstein’s speech Hitler would be appointed the chancellor of Germany.

Einstein had succumbed to what we now called the ‘lump of labor fallacy’ - the assumption that there is a finite amount of work for people to do - as did Keynes. Permanent mass-unemployment did not persist, and neither did Keynes prophecy of a 4-day-work week.

FEAR FEARING AUTOMATION

Ironically the fear of automation stoked by high profile figures like Einstein might well have unnecessarily dampened consumer sentiment by making unemployment feel inevitable and irreversible, it isn’t unreasonable to suggest this could well have made The Great Depression worse.

In ‘Narrative Economics’ Nobel Prize winning economist Robert J. Shiller suggested a ‘narrative epidemic’ around automation taking all the jobs likely exacerbated the depression of 1873, noting it was a similarly ‘epidemic narrative’ in the years leading up to the ‘The Great Depression.’

A few months after Einstein’s speech FDR would be elected President of the United States, in his inaugural address he uttered the famous words: “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” - a notion worth remembering as a new ‘narrative epidemic’ is set to take hold around AI and job automation.

Read more about the history of fears about automation in our previous post on the topic:

To read more about great minds making alarmist predictions about technologies, read our post on Norbert Wiener: